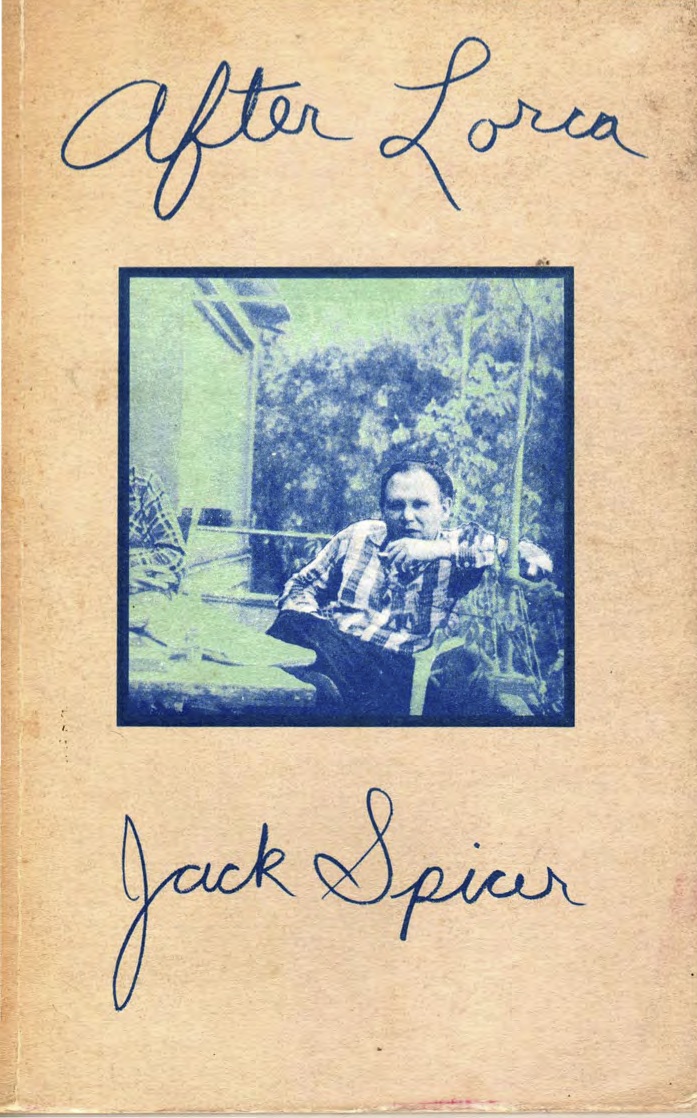

Cuneiform Press hosts a full PDF of the original chapbook of After Lorca

I want to sketch some rough ideas about the threshold where virtuality becomes materiality by comparing the San Francisco Renaissance poet Jack Spicer's discovery of a lemon, in one of his letters to the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca in After Lorca (1957), with the slow unveiling of a lemon in Hollis Frampton's minimalist film, Lemon (1969). The film and poem (indeed all of After Lorca) are perfectly suited to each other in large part because they address how we translate an object's temporal dimension into concrete form. What I mean by this is that like Spicer's desire to "make poems out of real objects," his lemon emerges through a process of discovery (133).

"Things do not connect they correspond. That is what makes it possible for a poet to translate real objects, to bring them across language as easily as he can bring them across time. That tree you saw in Spain is a tree I could never have seen in California, that lemon has a different smell and a different taste, BUT the answer is this--every place and every time has a real object correspond with your real object--that lemon may become this lemon, or it may even become this piece of seaweed, or this particular color gray in this ocean. One does not need to imagine that lemon; one needs to discover it" (Spicer 134).

The discovery is that this lemon is not equivalent to anything but itself at that moment in time. This is why objects for Spicer do not connect in the poem they co-respond. Frampton's film also "discovers" the lemon, makes it visible, not only by technically shadowing where its shape meets darkness, but by refusing to metaphoricize the lemon. His film fulfills Spicer's desire, to transport the object through time rather than translating its viscerality to a symbolic, timeless dimension. The lemon's material rudeness tingles the back of your tongue, and its stippled skin rubs across your eye as it slowly emerges from the shadows. In Lemon, the lemon is not a fruit we imagine, as much as its visceral presence is disclosed to us through its passage across our senses. This means that the lemon is not preserved (pun intended), but like taste, it arcs into and out of our awareness. Both Spicer and Frampton carefully negotiate how the lemon "is lead across time, not preserved against it," because too much light, whether visual or textual, would exceed perception's footholds in the rind and point the edges of its appearance elsewhere (Spicer 133). As Spicer put it, and Frampton's film visualizes, it is a different act than imagining, because "the imagination pictures the real. I would like to point to the real, disclose it..." (133). Read the poems, enjoy the film, and make lemonade!